If you’ve ever struggled getting to grips with webpack, now is a good time to get started. The stable release of webpack version 2 is out, and this guide will take you from zero to a functional webpack configuration. The end result will be a small, but working React application. The configuration will be expanded one item at a time and will be driven by error messages. By not starting out with a boilerplate, you’ll be able to understand what each part does, and thus be able to expand upon it yourself if new needs arise.

What is webpack?

If you are new to webpack, it is a system that uses loaders to preprocess files (javascript, css, images, and whatever other source files you can imagine) and pack them into bundles.

The advantages of this is that you can write modern javascript applications with modules, import your images and assets as if it were regular javascript and don’t worry about how it will be delivered to the javascript runtime in the end, whether you are targeting Node.js or a browser.

If you need it at some point, the documentation for webpack can be found at webpack.js.org.

What you’ll achieve

The goal of this post is to take you from nothing to a functioning webpack configuration for React with modern javascript, but will be easy to adapt to other technologies such as TypeScript and Angular. The application will use universal rendering and the configuration will cover both client and server applications as well as different output for different environments.

This guide will not be covering routing, styling, data fetching, testing or similar topics that are not directly connected to webpack.

Prerequisites

I assume some familiarity with React, namely: what it is, what it does, that components are the building blocks and that the JSX syntax is a way to render components. At a later stage, familiarity with Express is assumed. You should also know how npm works. And finally, you should have Node.js version 4 or newer installed.

If all of this is foreign to you, look at the React documentation, npm documentation, and when the need arises, the Express documentation.

With that out of the way, let’s start.

Getting up and running

To begin with, create a new folder for our project:

$ mkdir webpack-project && cd webpack-project

Then, initialise a new Node.js project with all the default settings:

$ npm init -y

The -y means “just say yes to everything”.

Once that is done, we will need webpack itself:

$ npm install --save-dev webpack

Webpack provides a binary in the node_modules folder that can be run to build our (currently non-existing) project:

$ ./node_modules/.bin/webpack

No configuration file found and no output filename configured via CLI option.

A configuration file could be named 'webpack.config.js' in the current directory.

...

Take a look at the error message: Webpack needs some configuration before it can know what to do. Create a file named webpack.config.js with this content:

module.exports = {}

Once again, run webpack and observe the error:

$ ./node_modules/.bin/webpack

...

Error: 'output.filename' is required, either in config file or as --output-filename

...

We need to specify where webpack should store its output. Make webpack.config.js look like this to do so:

module.exports = {

output: {

filename: 'bundle.js',

},

};

Again, run webpack and observe the error:

$ ./node_modules/.bin/webpack

Configuration file found but no entry configured.

...

Webpack needs something to build. Tell webpack to start the build with ./src/index.js by adding an entry property to webpack.config.js:

const path = require('path');

module.exports = {

entry: path.resolve('./src/index.js'),

output: {

filename: 'bundle.js',

},

};

Now, when you run webpack, the error message will look something like this:

ERROR in Entry module not found: Error: Can't resolve '/<path>/webpack-project/src/index.js' in '/<path>/webpack-project'

Make an empty file in src/index.js and run webpack again. The file bundle.js will appear, which means that webpack is working. But putting output files in the same folder will become cluttered quickly. To fix this, set output.path to path.resolve('./dist') in webpack.config.js:

const path = require('path');

module.exports = {

entry: path.resolve('./src/index.js'),

output: {

path: path.resolve('./dist'),

filename: 'bundle.js',

},

};

When you run webpack, it will now put the files in the dist folder, which is much better.

Now, lets make webpack output some actual code. Modify src/index.js:

console.log('it works')

See that Webpack is still building and that the output bundle works:

$ ./node_modules/.bin/webpack && node ./dist/bundle.js

Hash: b1420f60093b4525b97b

Version: webpack 2.2.1

Time: 52ms

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

bundle.js 2.53 kB 0 [emitted] main

[0] ./src/index.js 25 bytes {0} [built]

it works

Transforming code with Babel

Let’s add some modern javascript to src/index.js:

class A {

hello() { console.log('it works'); }

}

(new A).hello();

If you run a recent version of Node.js, this will run perfectly fine. If you want this code to work on older platforms or in browsers, the code will have to be transformed or “transpiled”. We can do this with a tool called Babel. Install Babel (babel-core), the command line interface (babel-cli) and a preset (babel-preset-env) for it:

$ npm install --save-dev babel-core babel-cli babel-preset-env

Babel presets are preconfigured collections of plugins and settings. The env preset automatically supplies the plugins necessary for a specified target platform to support the new javascript features that are deemed stable. We can configure Babel and its plugins and presets with a file called .babelrc:

{

"presets": [

[ "env", {

"targets": { "node": 4 }

} ]

]

}

By specifying a target of Node.js version 4, we can ensure that Babel actually does stuff with our code, no matter the version of Node.js you are using. You can transform the file by running Babel directly:

$ ./node_modules/.bin/babel src/index.js -o dist/bundle.js

Verify that Babel transformed the code by looking at the output file. Pay special attention to the part beginning with var A = ..., as that is our transformed application code. The rest is Babel’s responsibility:

$ cat ./dist/bundle.js

'use strict';

var _createClass = function () { function defineProperties(target, props) { for (var i = 0; i < props.length; i++) { var descriptor = props[i]; descriptor.enumerable = descriptor.enumerable || false; descriptor.configurable = true; if ("value" in descriptor) descriptor.writable = true; Object.defineProperty(target, descriptor.key, descriptor); } } return function (Constructor, protoProps, staticProps) { if (protoProps) defineProperties(Constructor.prototype, protoProps); if (staticProps) defineProperties(Constructor, staticProps); return Constructor; }; }();

function _classCallCheck(instance, Constructor) { if (!(instance instanceof Constructor)) { throw new TypeError("Cannot call a class as a function"); } }

var A = function () {

function A() {

_classCallCheck(this, A);

}

_createClass(A, [{

key: 'hello',

value: function hello() {

console.log('it works');

}

}]);

return A;

}();

new A().hello();

Run webpack and build the same code. This also works, but the output (stashed between the webpack specific code) is different:

$ ./node_modules/.bin/webpack && cat dist/bundle.js

/* start of file omitted for brevity */

class A {

hello() { console.log('it works'); }

}

(new A).hello();

/* end of file omitted for brevity */

Let’s make webpack output the same as the babel process. When you add the following section to the top level of the export in webpack.config.js, you are telling webpack how to process modules whose filename match the regular expression in test. In this case webpack will process all javascript files with Babel using the loader babel-loader`:

module: {

rules: [

{

test: /\.js$/,

include: path.resolve('./src'),

loader: 'babel-loader',

}

],

},

Before you can run webpack, the loader needs to be installed:

$ npm install --save-dev babel-loader

If you now run webpack and take a look at the output in dist/bundle.js, you’ll see that it matches the output from running the babel process directly, as we did earlier. Webpack is now correctly using Babel to process the javascript.

Refactoring

We’ve already come a long way, but before we get something that is more useful, lets clean up a bit.

Instead of calling webpack directly, add a build script in package.json that calls webpack. That way npm run build can be used instead of having to type ./node_modules/.bin/webpack:

...

"scripts": {

"build": "webpack"

},

...

I also suggest running npm uninstall --save-dev babel-cli, because it won’t be used any longer.

Change the filename of .babelrc to babelrc.js and modify it like so, since it’s no longer required to be JSON:

module.exports = {

presets: [

[ 'env', {

targets: { node: 'current' }

} ]

]

}

Ensure that you also changed the Node.js target.

Babel only natively knows about .babelrc files, so to pick up the new file, the babel-loader-rule in webpack.config.js needs some configuration:

{

test: /\.js$/,

include: path.resolve('./src'),

loader: 'babel-loader',

query: require('./babelrc.js'), // Add this

}

This will all make it easier to extract, reuse and extend the Babel configuration at a later stage.

Rendering with React

Now that we have a functional foundation, let’s add React.

$ npm install --save react

Put some React code in src/index.js:

import React from 'react';

class HelloWorld extends React.Component {

render() {

return <h1>Hello, World!</h1>;

}

}

console.log(new HelloWorld().render());

Try to build it with webpack:

$ npm run build

Notice that it fails on the <h1> from our component. To convert the JSX tag in the React code to something that Node.js and browsers understand, an additional preset for babel is needed:

$ npm install --save-dev babel-preset-react

Add it to the presets attribute of the babel configuration:

module.exports = {

presets: [

[ 'env', {

targets: { node: 'current' }

} ],

'react', // Add this

],

}

Build the project, and verify that the resulting code actually works now:

$ npm run build && node ./dist/bundle.js

...

{ '$$typeof': Symbol(react.element),

type: 'h1',

key: null,

ref: null,

props: { children: 'Hello, World!' },

_owner: null,

_store: {} }

Because we would like to use React to build websites, let’s get the component rendered in a browser instead of a terminal.

First, we need some basic HTML to bootstrap the process. Put the following in src/index.html:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<title>React App</title>

</head>

<body>

<script src="../dist/bundle.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

If you open this in your browser and open the Developer Console, you should see the same output as you saw in your terminal, just represented in a different way. If you use Chrome, open the console by pressing Ctrl + Shift + J on Windows or Cmd + Opt + J on MacOS.

To get the component to render, start by refactoring a bit:

- Change the filename of

src/index.jstosrc/HelloWorld.js. - Remove the

console.log. - Export the

class, so it can be used from another file.

The contents of HelloWorld.js should look like this:

import React from 'react';

export default class HelloWorld extends React.Component {

render() {

return <h1>Hello, World!</h1>;

}

}

To have React render into the DOM, we will need the react-dom package:

$ npm install --save react-dom

We’ll also need a new file to serve as the entrypoint for the browser. The reason for creating a seperate entrypoint is to make it easier to make the application universal in the future.

ReactDOM needs somewhere to render its results to. Add the following to the <body> in src/index.html:

<div id='root'></div>

Now, add the browser entrypoint in src/index.browser.js to get React to render and control the DOM under <div id='root'></div>:

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import HelloWorld from './HelloWorld';

const root = document.getElementById('root');

ReactDOM.render(<HelloWorld />, root);

Try to compile (with npm run build) and notice that it doesn’t work anymore. To get webpack to build our bundle again, change the entrypoint in webpack.config.js to ./src/index.browser.js:

module.exports = {

entry: path.resolve('./src/index.browser.js'),

...

};

At the same time, change the target in babelrc.js to browsers instead of Node.js:

module.exports = {

presets: [

[ 'env', {

targets: { browsers: ['> 5%', 'last 2 versions'] }

} ],

'react',

],

}

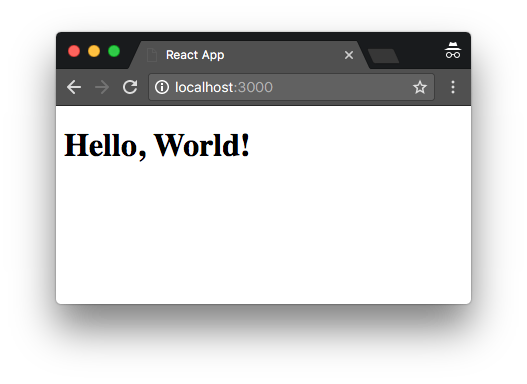

Build the project, refresh index.html in the browser and you should see a pretty <h1>Hello World</h1> rendered in all its glory.

If you do not already have the React DevTools installed, visit https://fb.me/react-devtools and do so.

Once it has been installed, you will see the following message in the developer console:

Download the React DevTools and use an HTTP server (instead of a file: URL) for a better development experience

Let’s fix the error about not using an HTTP server.

Adding a server

We’ll use the Express webserver, which is the de facto standard server for Node.js, to serve the application:

$ npm install --save express

Add src/index.server.js with the following:

const path = require('path');

const express = require('express');

const app = express();

app.get('*', (req, res) => {

res.sendFile(path.resolve(__dirname, './index.html'));

});

app.listen(3000, () => {

console.log('React app listening on port 3000!')

});

Run the server with node ./src/index.server.js, open localhost:3000 and you’ll notice that it doesn’t contain the “Hello World” text. If you open the Developer Tools, you can see that the bundle.js file isn’t transferred correctly. This is caused by every request being served by the app.get('*', ...), which always sends the contents of index.html. To fix this, add the following line to index.server.js, just before app.get('*', ...):

app.use('/static', express.static(path.resolve(__dirname, '../dist')));

This piece of middleware, as it is called, will serve the files located in our dist folder from /static. You will also need to change the src attribute of the <script> tag in index.html to match the correct path:

<script src="/static/bundle.js"></script>

Restart the server, reload your browser and behold “Hello World” in all its glory again.

Modernizing the server

To keep the server code consistent with the client code, let’s change the const module = require('module') to import module from 'module'. Modify index.server.js to look like:

import path from 'path';

import express from 'express';

...

Besides consistency, import statements have a few advantages compared to require() calls. One of them is that the import statements can be analyzed statically whereas require() cannot. We’ll take advantage of this later.

If you try to run the server, you’ll notice that it doesn’t work anymore:

$ node ./src/index.server.js

...

SyntaxError: Unexpected token import

...

Node.js doesn’t understand the import. For it to work, we need to build the server with webpack as well. Because the import statements require a processing step, we unfortunately need to keep using const … = require('…') in the webpack config. You could add a separate step to process the config file as well, but then the build system becomes convoluted.

To process the server, we can utilize that a webpack configuration can consist of multiple configurations if they are exported as an array. Add a copy of the current configuration and export both, changing the entrypoint, output filename and target:

const path = require('path');

const webpack = require('webpack');

const clientConfig = {

entry: path.resolve('./src/index.browser.js'),

output: {

path: path.resolve('./dist'),

filename: 'bundle.js',

},

module: {

rules: [

{

test: /\.js$/,

include: path.resolve('./src'),

loader: 'babel-loader',

query: require('./babelrc.js'),

}

],

},

};

const serverConfig = {

target: 'node',

entry: path.resolve('./src/index.server.js'),

output: {

path: path.resolve('./dist'),

filename: 'server.js',

},

module: {

rules: [

{

test: /\.js$/,

include: path.resolve('./src'),

loader: 'babel-loader',

query: require('./babelrc.js'),

}

],

},

};

// Notice that both configurations are exported

module.exports = [clientConfig, serverConfig];

The target property specifies how webpack will load the built modules and dependencies. The default is web, which works fine for the client side bundle. The server runs in a Node.js context and thus needed target: 'node', to have the correct output.

The configuration is a bit verbose and mostly just consists of duplicated code, but we will fix that later. For now, build both the client and the server bundle:

$ npm run build

Ignore the error warning from ./~/express/lib/view.js about a critical dependency for now. It will be cleared up later. First, try to run the compiled server:

$ node ./dist/server.js

When you open localhost:3000, you’ll see:

Error: ENOENT: no such file or directory, stat '/index.html'

Note that the error message on Windows will look slighty different.

It seems that the Express server can’t find the HTML file we are trying to send as a response to the browser. This is caused by the usage of __dirname and a (for the moment) little-documented fact of webpack: A number of Node.js features are replaced or transformed by webpack, and __dirname is one of them. If you add a toplevel node attribute to the server webpack configuration, you can control what happens with, for instance, __dirname. By experimenting, you will discover that setting node.__dirname to nothing, true or false, results in varying functionality:

- Not set or

undefined:__dirnameis set to/. true: sets_dirnameto what it was in the source file../src/in our case.false: set__dirnameto the regular Node.js functionality. In our case, it would resolve to./dist/.

To make the source code easier to reason about when it comes to filepaths, we’ll set node.__dirname to true in the serverConfig:

const serverConfig = {

target: 'node',

node: {

__dirname: true

},

...

};

That way the path that is currently present in src/index.server.js will continue to work when the bundle has been built. Once you’ve set the attribute in the webpack config, make a new build, restart the server and verify that “Hello World” is back in the browser.

Differentiating Babel configuration for the different runtimes

Right now, the Babel configuration is the same for the Node.js target as well as the browsers. This works, but isn’t correct since babelrc.js contains the line:

targets: { browsers: ['> 5%', 'last 2 versions'] }

For the Node.js bundle, Babel could output non-functioning code if the capabilities of Node.js are different to those of the targeted browsers. To fix it, change babelrc.js to export a function that can return either a browser configuration or a Node.js configuration:

module.exports = ({ server } = {}) => ({

presets: [

[ 'env', {

targets: server ? { node: 'current' } : { browsers: ['> 5%', 'last 2 versions'] }

} ],

'react',

],

});

Then, put the following at the top of webpack.config.js:

const createBabelConfig = require('./babelrc');

Finally, replace the query: require('./babelrc) in the clientConfig with:

query: createBabelConfig(),

The corresponding line in serverConfig should be replaced with:

query: createBabelConfig({ server: true }),

Now Babel includes the correct required plugins and presets for the two different environments. Make a new build, restart the server and verify that everything still works.

Optimizing what is bundled

If we return to the error message that was emitted by ./~/express/lib/view.js:

Critical dependency: the request of a dependency is an expression

The code that causes the warning doesn’t matter at the moment, but the warning occurs because webpack is trying to include the Node.js dependencies and build those as well. In general, these are already built, so to avoid this, it’s possible to specify externals. Externals are modules that webpack won’t include in a build. The easiest way to omit our Node.js dependencies from the build is to use the package webpack-node-externals:

$ npm install --save-dev webpack-node-externals

It needs to be added to the server webpack config:

const nodeExternals = require('webpack-node-externals');

...

const serverConfig = {

target: 'node',

externals: [ nodeExternals() ],

...

When you make a build now, the dependencies won’t be bundled with the application code and the error message has disappeared. Refresh your browser and verify that “Hello, World!” still shows up.

The next step is making our server render the React code instead of just serving static HTML.

Getting to universal React rendering

The first step in converting the application to being universal (what was previously known as isomorphic) is rendering the DOM on the server, before the browser takes over. The react-dom package contains a server module in react-dom/server that contains functionality for exactly this purpose.

We can use the exported renderToString method to render the markup for the app. To do that, we need the following imports in index.server.js:

import React from 'react';

import ReactServer from 'react-dom/server';

import HelloWorld from './HelloWorld';

The ExpressJS handler then needs to return the static markup instead of sending the content of index.html. To achieve this, replace the app.get('*', …) block with the following:

app.get('*', (req, res) => {

const markup = ReactServer.renderToString(<HelloWorld />);

res.send(markup);

});

If you build and run the server, you should still have “Hello World” in your browser. But the skeleton of the HTML is missing and React isn’t loaded, so any dynamic features you implement won’t work.

To fix this, the markup that is rendered needs to be inserted into <div id='root'></div> in index.html. An easy way to achieve that is to insert some text that can be replaced with the markup. Change the <div> to look like this:

<div id='root'>$react</div>

Then, we’ll use the fs module in Node.JS to read index.html and replace $react with the React markup:

import fs from 'fs';

...

app.get('*', (req, res) => {

const html = fs.readFileSync(path.resolve(__dirname, './index.html')).toString();

const markup = ReactServer.renderToString(<HelloWorld />);

res.send(html.replace('$react', markup));

});

Build, start the server and refresh your browser. Congratulations, you’ve made a universal React app!

Adding different environments

At some point, the need will arise for different configurations for different environments. React contains quite a lot of code that should be removed before running the code in production environments. It will reduce the size of the bundle that is sent to users as well as speed up runtime. Adding support for different environments will ensure that these plugins and libraries won’t be enabled unless they are needed.

The first step is creating a new script in package.json for building the production version of our app:

...

"scripts": {

"build": "webpack",

"build:prod": "cross-env NODE_ENV=production webpack"

},

...

This will allow us to differentiate what the webpack config will look like based on the value of process.env.NODE_ENV.

It uses the cross-env library to set environment variables, so it works whether you use Windows, MacOS or Linux. It needs to be installed before we can use it:

$ npm install --save-dev cross-env

The first thing we want to do is enable minifaction of the output bundle. That can be done by having a plugin in the production environment handle that task. Webpack comes with a bundled plugin for UglifyJS, which is a code minifier. Unfortunately UglifyJS doesn’t yet work with modern javascript such as classes. That means that we need Babel to transform more code than it might actually have to, so Uglify can make the code smaller. We need to ensure that Babel will transform the features Uglify doesn’t understand by targeting platforms that also don’t understand them.

Change the node and browsers targets in babelrc.js to the following:

module.exports = ({ server } = {}) => ({

presets: [

[ 'env', {

targets: server ? { node: 4 } : { browsers: ['> 5%', 'last 2 versions', 'ie 11'] }

} ],

'react',

],

});

First, add a shorthand determining if we are in the correct environment at the top of webpack.config.js:

const PRODUCTION = process.env.NODE_ENV === 'production';

Then, make a shorthand for the minifier at the top of webpack.config.js:

const MinifierPlugin = webpack.optimize.UglifyJsPlugin;

Finally, add the following property to both the clientConfig and serverConfig:

plugins: [

PRODUCTION && new MinifierPlugin(),

].filter(e => e),

The plugins array should only contain functions, so the .filter(e => e) ensures that non-matching plugins are removed before webpack runs, because they will be falsy.

If you run npm run build you should see something like the following:

> webpack

Hash: bc258b6bf8c1137ebb662ad6dbb351449aa18a14

Version: webpack 2.2.1

Child

Hash: bc258b6bf8c1137ebb66

Time: 1101ms

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

bundle.js 728 kB 0 [emitted] [big] main

[6] ./~/fbjs/lib/ExecutionEnvironment.js 1.06 kB {0} [built]

[8] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactInstrumentation.js 601 bytes {0} [built]

[10] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactUpdates.js 9.53 kB {0} [built]

[19] ./~/react/lib/React.js 2.69 kB {0} [built]

[52] ./~/react/react.js 56 bytes {0} [built]

[80] ./src/HelloWorld.js 2.44 kB {0} [built]

[81] ./~/react-dom/index.js 59 bytes {0} [built]

[109] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactDOM.js 5.14 kB {0} [built]

[169] ./~/react/lib/ReactChildren.js 6.19 kB {0} [built]

[170] ./~/react/lib/ReactClass.js 26.5 kB {0} [built]

[171] ./~/react/lib/ReactDOMFactories.js 5.53 kB {0} [built]

[172] ./~/react/lib/ReactPropTypes.js 15.8 kB {0} [built]

[173] ./~/react/lib/ReactPureComponent.js 1.32 kB {0} [built]

[174] ./~/react/lib/ReactVersion.js 350 bytes {0} [built]

[178] ./src/index.browser.js 702 bytes {0} [built]

+ 164 hidden modules

Child

Hash: 2ad6dbb351449aa18a14

Time: 442ms

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

server.js 6.98 kB 0 [emitted] main

[1] ./src/HelloWorld.js 2.44 kB {0} [built]

[6] ./src/index.server.js 1.3 kB {0} [built]

+ 5 hidden modules

Take note of the two bundle sizes: 728 kB and 6.98 kB and note that the sizes on your machine might be a little bit different.

Let’s run npm run build:prod:

> NODE_ENV=production webpack

Hash: a385dc2490482dd5e6e5d311fe1390e1e9901617

Version: webpack 2.2.1

Child

Hash: a385dc2490482dd5e6e5

Time: 6924ms

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

bundle.js 221 kB 0 [emitted] main

[6] ./~/fbjs/lib/ExecutionEnvironment.js 1.06 kB {0} [built]

[8] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactInstrumentation.js 601 bytes {0} [built]

[10] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactUpdates.js 9.53 kB {0} [built]

[19] ./~/react/lib/React.js 2.69 kB {0} [built]

[52] ./~/react/react.js 56 bytes {0} [built]

[80] ./src/HelloWorld.js 2.25 kB {0} [built]

[81] ./~/react-dom/index.js 59 bytes {0} [built]

[109] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactDOM.js 5.14 kB {0} [built]

[169] ./~/react/lib/ReactChildren.js 6.19 kB {0} [built]

[170] ./~/react/lib/ReactClass.js 26.5 kB {0} [built]

[171] ./~/react/lib/ReactDOMFactories.js 5.53 kB {0} [built]

[172] ./~/react/lib/ReactPropTypes.js 15.8 kB {0} [built]

[173] ./~/react/lib/ReactPureComponent.js 1.32 kB {0} [built]

[174] ./~/react/lib/ReactVersion.js 350 bytes {0} [built]

[178] ./src/index.browser.js 520 bytes {0} [built]

+ 164 hidden modules

Child

Hash: d311fe1390e1e9901617

Time: 585ms

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

server.js 2.53 kB 0 [emitted] main

[1] ./src/HelloWorld.js 2.25 kB {0} [built]

[6] ./src/index.server.js 1.12 kB {0} [built]

+ 5 hidden modules

The sizes have been reduced to 221 kB and 2.53 kB. A reduction of 70% and 63%. But it can become even lower.

NOTE FOR THE ADVENTUROUS: If you want to try out a minifier that understands modern javascript, you can use the babili minifier, based on Babel. It can either be installed directly as a Babel preset or as a webpack plugin. The preset works on original source files whereas the webpack plugin works on bundled output. In this case, you should use the plugin because it provides better results for our use case with bundled output.

First, you would need to install it:

$ npm install --save-dev babili-webpack-plugin

Then you would need to change the declaration of MinifierPlugin to point to Babili:

const MinifierPlugin = require('babili-webpack-plugin');

And lastly, you should change the node target in babelrc.js from 4 to current. You could also remove support for IE 11 if you want:

module.exports = ({ server } = {}) => ({

presets: [

[ 'env', {

targets: server ? { node: 'current' } : { browsers: ['> 5%', 'last 2 versions'] }

} ],

'react',

],

});

But do beware: Babili has a few bugs.

And now, back to the regular schedule again.

Replacing content in the source code

The React code contains code paths that are put in if-blocks like the following:

if (process.env.NODE_ENV !== 'production') {

...

}

These aren’t removed by the minifier because it cannot know that process.env.NODE_ENV is equal to production. To fix this, we can add another webpack plugin, that defines constants in the code. It also enables us to keep parity between the server and the client, by allowing the use of process.env.NODE_ENV (and friends), even in client-side code. Add the following to both of the plugins arrays:

new webpack.DefinePlugin({

'process.env.NODE_ENV': JSON.stringify(process.env.NODE_ENV)

})

Then, run npm run build:prod again:

> NODE_ENV=production webpack

Hash: aae5fecee2adc6a2592fd311fe1390e1e9901617

Version: webpack 2.2.1

Child

Hash: aae5fecee2adc6a2592f

Time: 6295ms

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

bundle.js 144 kB 0 [emitted] main

[3] ./~/object-assign/index.js 2.11 kB {0} [built]

[15] ./~/react/lib/React.js 2.69 kB {0} [built]

[16] ./~/react/lib/ReactElement.js 11.2 kB {0} [built]

[47] ./~/react/react.js 56 bytes {0} [built]

[77] ./src/HelloWorld.js 2.25 kB {0} [built]

[78] ./~/react-dom/index.js 59 bytes {0} [built]

[104] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactDOM.js 5.14 kB {0} [built]

[146] ./~/react-dom/lib/findDOMNode.js 2.46 kB {0} [built]

[154] ./~/react-dom/lib/renderSubtreeIntoContainer.js 422 bytes {0} [built]

[158] ./~/react/lib/ReactClass.js 26.5 kB {0} [built]

[159] ./~/react/lib/ReactDOMFactories.js 5.53 kB {0} [built]

[160] ./~/react/lib/ReactPropTypes.js 15.8 kB {0} [built]

[162] ./~/react/lib/ReactPureComponent.js 1.32 kB {0} [built]

[163] ./~/react/lib/ReactVersion.js 350 bytes {0} [built]

[166] ./src/index.browser.js 520 bytes {0} [built]

+ 152 hidden modules

Child

Hash: d311fe1390e1e9901617

Time: 656ms

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

server.js 2.53 kB 0 [emitted] main

[1] ./src/HelloWorld.js 2.25 kB {0} [built]

[6] ./src/index.server.js 1.12 kB {0} [built]

+ 5 hidden modules

The browser script in bundle.js has been reduced even further to 144 kB.

Note, that while it might seem weird to minify the server side code, it actually has a reason. Every NodeJS function with a body of less than 600 characters, including comments, will be inlined. 601 characters and higher and the function will be called as a function, which incurs a substantial overhead. To be safe, minify.

Now that we’ve spent a lot of time optimizing our browser bundle and our server application code, we should probably also use optimized React builds on the server. If you look in the dist folders of react and react-dom you’ll see the following files:

$ tree ./node_modules/react*/dist

node_modules/react-dom/dist

├── react-dom-server.js

├── react-dom-server.min.js

├── react-dom.js

└── react-dom.min.js

node_modules/react/dist

├── react-with-addons.js

├── react-with-addons.min.js

├── react.js

└── react.min.js

The files we are interested in are react-dom-server.min.js, which corresponds to the react-dom/server module and react.min.js which corresponds to the react module.

If we want the optimized builds, we need to include them in our bundle output. To do this, we can utilize the resolve.alias property in the serverConfig in webpack.config.js to map the React libraries to their minified versions:

resolve: {

alias: PRODUCTION ? {

'react': 'react/dist/react.min.js',

'react-dom/server': 'react-dom/dist/react-dom-server.min.js',

} : {},

}

If you make a build, you can see that the server bundle hasn’t increased in size, even though we wanted to include react and react-dom in it. It is caused by the externals property which specifies that react and react-dom shouldn’t be included in the server bundle after all. The result is that the alias setting has no effect. The fix is fortunately simple. The method supplied by the webpack-node-externals module takes an optional options object as parameter. One of the properties available is whitelist, which specifies which modules shouldn’t be marked as external, even though they are Node.js dependencies. By changing nodeExternals() to the following, react and react-dom/server will be included in the bundle with their minified files when making a production build:

externals: [ nodeExternals({

whitelist: PRODUCTION ? [ 'react', 'react-dom/server' ] : []

}) ]

By looking a the output from npm run build:prod you can see that the React modules are now included in the bundle:

> NODE_ENV=production webpack

Hash: aae5fecee2adc6a2592fcfdc37c677ebf08b91e1

Version: webpack 2.2.1

...

Child

Hash: cfdc37c677ebf08b91e1

Time: 6883ms

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

server.js 142 kB 0 [emitted] main

[0] ./~/react/dist/react.min.js 21.2 kB {0} [built]

[1] ./src/HelloWorld.js 2.25 kB {0} [built]

[2] ./~/react-dom/dist/react-dom-server.min.js 119 kB {0} [built]

[6] ./src/index.server.js 1.12 kB {0} [built]

+ 3 hidden modules

One thing sticks out, though. Since we are already using a minifier on the code, it doesn’t really make sense to use the minified files. Doing so also makes the webpack configuration more complicated. Remove the resolve.alias, make a production build and let webpack do its thing:

> NODE_ENV=production webpack

Hash: aae5fecee2adc6a2592f05e9daf5ea9c0e7007f7

Version: webpack 2.2.1

...

Child

Hash: 05e9daf5ea9c0e7007f7

Time: 5542ms

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

server.js 129 kB 0 [emitted] main

[11] ./~/react/lib/ReactElement.js 11.2 kB {0} [built]

[42] ./~/react/lib/ReactComponent.js 4.61 kB {0} [built]

[45] ./~/react/react.js 56 bytes {0} [built]

[75] ./src/HelloWorld.js 2.25 kB {0} [built]

[76] ./~/react-dom/server.js 65 bytes {0} [built]

[100] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactDOMServer.js 735 bytes {0} [built]

[104] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactDefaultInjection.js 3.5 kB {0} [built]

[118] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactServerRendering.js 3.47 kB {0} [built]

[120] ./~/react-dom/lib/ReactVersion.js 350 bytes {0} [built]

[145] ./~/react/lib/React.js 2.69 kB {0} [built]

[146] ./~/react/lib/ReactChildren.js 6.19 kB {0} [built]

[147] ./~/react/lib/ReactClass.js 26.5 kB {0} [built]

[148] ./~/react/lib/ReactDOMFactories.js 5.53 kB {0} [built]

[151] ./~/react/lib/ReactPureComponent.js 1.32 kB {0} [built]

[161] ./src/index.server.js 1.12 kB {0} [built]

+ 147 hidden modules

In fact, the bundle ended up being smaller on top of the configuration being smaller. Win-win.

Whether or not it is worth to include React in the server bundle or not will differ from application to application and you should perform benchmarks to be sure.

Utilizing “tree shaking” in webpack

Tree shaking is a method to eliminate code that is never used (in comparison to dead code, which it code that is impossible to reach). Webpack 2 understands the modern javascript module imports and exports and can determine what is actually used. What is not used will not be included in the final bundle. Enabling tree shaking is easy, we just need to tell Babel not to transform javascript modules. Add a "modules": false property to the configuration of the env preset in babelrc.js:

module.exports = ({ server } = {}) => ({

presets: [

[ 'env', {

targets: server ? { node: 'current' } : { browsers: ['> 5%', 'last 2 versions'] },

modules: false,

} ],

'react',

],

});

Note that tree shaking only works with import statements and not require() calls, because import statements are, as mentioned earlier, statically analyzable. Tree shaking will not make a difference in the bundle sizes the project in its current state. Once you write more code and import more packages, tree shaking will start to have an effect.

Getting more information during development

Webpack isn’t the only tool in the pipeline that can have differing configurations based on environments. Babel can also enable plugins in specific environments only by nesting the configuration under the env.<environment> key like so:

{

presets: [ .. ],

plugins: [ ... ],

env: {

development: {

plugins: [/* plugins only available in development environment */ ]

}

}

}

If you look at the source of babel-preset-react that we have activated in our Babel configuration, you will find two very useful plugins that have been commented out. The reason is that the development environment is the default for Babel and these plugins shouldn’t be enabled in production builds. Since we have a specific build for production that properly sets NODE_ENV the plugins can safely be added to our configuration. To ensure that the plugins are working, let’s first add an ‘error’. Change the render method of HelloWorld.js to the following:

render() {

return <h1>{ ["Hello, ", "World!"].map(text => <span>{ text }</span>) }</h1>;

}

This code doesn’t set the key property of the children in the loop like it should. If you make non-production build, view the site in your browser and open the Developer Console, something like the following will show up:

Warning: Each child in an array or iterator should have a unique "key" prop. Check the render method of `HelloWorld`. See https://fb.me/react-warning-keys for more information.

in span (created by HelloWorld)

in HelloWorld

Not that informative, since we can’t tell in which file the error originated, so let’s install those plugins:

$ npm install --save-dev babel-plugin-transform-react-jsx-self \

babel-plugin-transform-react-jsx-source

They also need to be added to babelrc.js:

module.exports = ({ server } = {}) => ({

presets: [ ... ],

env: {

development: {

plugins: [

"babel-plugin-transform-react-jsx-self",

"babel-plugin-transform-react-jsx-source",

]

},

}

});

Re-build, refresh the browser and the message in the console now looks like:

Warning: Each child in an array or iterator should have a unique "key" prop. Check the render method of `HelloWorld`. See https://fb.me/react-warning-keys for more information.

in span (at HelloWorld.js:6)

in HelloWorld (at index.browser.js:7)

Much better, as we know actually have a chance of finding the location of our bug.

Adding source maps

To aid the bug finding even more, we can add a last property to the webpack client config. devtool specifies which type of source map, if any, is generated by webpack. The functionality is built in and doesn’t require any new packages.

For development, cheap-module-eval-source-map is a good choice as it is fairly fast, shows line numbers and most importantly shows the original code. For production, source-map is a safe choice. It’s pretty slow, but gives good results. The slowness doesn’t matter as much as production builds are not made that often. Add the following to clientConfig:

devtool: PRODUCTION ? 'source-map' : 'cheap-module-eval-source-map',

For the server, source maps is a bit more muddy. The only devtool option that I have found to work is source-map. But to actually get them to show, we need two additional tools: One that maps source maps to Node.js stack trace API and another that enables this tool for every output file.

The first is source-map-support, so let’s install it:

$ npm install --save-dev source-map-support

To make it, the plugin needs to have some code inserted at the top of all the output files. Webpack includes a plugin called BannerPlugin that does exactly this: Insert text at the top of every output file. Add it to the plugins array in the serverConfig object:

plugins: [

...

new webpack.BannerPlugin({

banner: 'require("source-map-support").install();',

raw: true,

entryOnly: false,

}),

]

Finally, set a devtool in the serverConfig:

devtool: 'source-map',

If you make a build and errors occur in the server code, the original filename and line numbers will be printed. If you run the server with --inspect and open the URL Chrome Developer Tools that shows up, you can even see where output like console.log originates:

node --inspect ./dist/server.js

Webpack supports a range of different types of source maps. They each have their own set of advantages and disadvantages and some of them might suit your use case better than others.

Building continuously

It is a bit annoying to make all those builds after every change. Luckily, you can tell webpack to watch your filesystem for changes and rebuild when they occur and doing so is easy. Add a new script to package.json:

...

"scripts": {

"build": "webpack",

"build:prod": "cross-env NODE_ENV=production webpack",

"watch": "webpack --watch"

},

...

Start the watch script and notice that it makes an initial build:

$ npm run watch

If you make changes to any of your source files, webpack will make a new build automatically. You will unfortunately still need to restart the server script when that has been updated. Let’s change that next.

We can use a package called nodemon to handle running the server script and restart it when the compiled file changes. Let’s install it:

$ npm install --save-dev nodemon

Add another script to package.json:

...

"watch": "webpack --watch",

"serve": "nodemon -w dist/server.js dist/server.js"

...

The -w <path> argument tells nodemon what to monitor for changes. The second instance of dist/server.js indicates which file should be run.

If you run npm run watch in one terminal instance and npm run serve in another, any changes you make to your server should now also be picked up automatically. There are a lot of ways to run these two commands in parallel. We’ll use the package concurrently to avoid having to deal with cross platform differences. Install it with npm:

$ npm install --save-dev concurrently

And add a new script to run it:

...

"watch": "webpack --watch",

"serve": "nodemon -w dist/server.js dist/server.js",

"watch-and-serve": "concurrently --kill-others \"npm run watch\" \"npm run serve\""

...

This starts the two npm commands at the same time, and kills the other should one of them crash (--kill-others).

With that done, all that is left is spring cleaning.

Final cleanup

The two different webpack configurations, each with their own environmental setup contains a lot of code duplication and could use a refactoring. A lot of what can be done is a matter of style. Multi-file solutions or dependency on tooling like webpack-merge are some of the options. Try to experiment and see what you prefer. When the configuration is as simple as it is here, I like something like this:

const path = require('path');

const webpack = require('webpack');

const nodeExternals = require('webpack-node-externals');

const MinifierPlugin = webpack.optimize.UglifyJSPlugin;

const createBabelConfig = require('./babelrc');

const PRODUCTION = process.env.NODE_ENV === 'production';

const filterFalsy = (arr) => arr.filter(e => e);

const createPlugins = ({ server } = {}) => filterFalsy([

PRODUCTION && new MinifierPlugin(),

new webpack.DefinePlugin({

'process.env.NODE_ENV': JSON.stringify(process.env.NODE_ENV)

}),

server && new webpack.BannerPlugin({

banner: 'require("source-map-support").install();',

raw: true,

entryOnly: false,

})

]);

const createModule = (babelOptions) => ({

rules: [

{

test: /\.js$/,

include: path.resolve('./src'),

loader: 'babel-loader',

query: createBabelConfig(babelOptions),

}

],

});

const createExternals = ({ server } = {}) => filterFalsy([

server && nodeExternals({

whitelist: PRODUCTION ? [ 'react', 'react-dom/server' ] : []

})

]);

const createDevTool = ({ server } = {}) =>

PRODUCTION || server ? 'source-map' : 'cheap-module-eval-source-map';

const createBase = (options) => ({

module: createModule(options),

externals: createExternals(options),

plugins: createPlugins(options),

devtool: createDevTool(options),

});

const clientConfig = Object.assign({

target: 'web',

entry: path.resolve(__dirname, './src/index.browser.js'),

output: {

path: path.resolve(__dirname, './dist'),

filename: 'bundle.js',

},

}, createBase({ server: false }));

const serverConfig = Object.assign({

target: 'node',

entry: path.resolve('./src/index.server.js'),

output: {

path: path.resolve('./dist'),

filename: 'server.js',

},

node: {

__dirname: true,

},

}, createBase({ server: true }));

module.exports = [clientConfig, serverConfig];

Since your taste might not equal mine, this is your chance to make the configuration your own.

And with that, we are done.

What has been achieved?

If you’ve followed along, you should:

- Know how to configure Babel and how to differentiate between environments

- Utilize Babel presets and plugins to transform the source code

- Utilize environments to alter the webpack bundle outputs

- Know how to redirect modules with aliases

- Be able to add content to the output files or replace content in the source files

- Know how to add source maps and know that there are different types

- Be able to build server side bundles as well as client side bundles

- How to make webpack watch your code and automatically restart the output application

- Have a feeling for how to build a modular webpack config

I hope this guide has given you the knowledge to be able to better understand other Babel- and webpack configurations. This will let you choose the features you want in your webpack configuration, instead of having to rely on boilerplates and starter kits. And by knowing what goes on underneath, you can make a more informed decision, should you choose to use a starter kit or boilerplate.

If you are interested in seeing how other people do it, some good places to look are create-react-app and nwb.

Even though a lot has been covered, here are some other things that you might still want to learn about:

- How to make webpack reload only the modules that have changed using “Hot Module Reloading” and

webpack-dev-middleware - How to put the webpack and Babel configurations in an external package which can be versioned and kept separate from the code

- How to split webpack bundles into different parts, so you can wait with transmitting the code until the user needs it

- How to name your output bundles so you can aggressively cache them

Have fun!

Thanks to Emil Christensen for reading drafts of this.